The best Kanye West line of 2018 isn’t even a Kanye line. It’s on his brilliant collaborative album with Kid Cudi, Kids See Ghosts. Cudi, who has been candid about his struggles with mental illness but hadn’t been quite so transparent in his music, sings on “Reborn”: “At times wonder my purpose / Easy then to feel worthless / But peace is something that starts with me.” He repeats the words “with me,” turning them into a mantra and a critical reminder to both himself and the listener. He sounds relieved just to say it out loud.

This isn’t entirely new, of course. Music artists plumb the depths of their inner lives, especially in a confessional and verbally gymnastic genre like rap. “Things we hear currently tend to have predecessors in the history of rap music,” says A.D. Carson, a professor of hip-hop at the University of Virginia and a rap performer. “We can look at rappers who have had open and frank discussions about things we would fit under the broader category of music that engages with topics of mental health.”

He points to Geto Boys’ 1991 “Mind Playing Tricks on Me” (“I’m paranoid, sleepin’ with my finger on the trigger”) and Jay-Z’s 2002 “Song Cry,” in which the MC makes more covert references to being “sick” (“Though I can’t let you know it, pride won’t let me show it,” one line goes). “He’s emotionally muted, so he’s going to make the song cry,” Carson explains. “He’s rapping to somehow stand in for what he’s not able to do to work through his emotions about a complicated abusive relationship.”

Something has profoundly shifted. This year’s head-on confrontation with mental illness, and the treatment of it as such, “reflects the ways society at large seems to be more engaged in discussions of mental health,” Carson adds.

An undeniable shadow hangs over this awareness. Several prominent rap stars died in 2018, including the rising sensation Mac Miller, who died at 26 from an overdose of fentanyl, cocaine, and alcohol. That was shocking but sadly not surprising, given that Miller himself was forthcoming about his demons during his life.

The reaction to Miller’s demise, however, did feel like a revelation. There was an outpouring of support from Donald Glover, Chance the Rapper, and Vince Staples. Notably, French Montana and Bow Wow expressed real concern about drug culture in hip-hop without caring that they might look “soft.” Miller’s ex Ariana Grande sings on her latest smash “Thank U, Next,” “Wish I could say thank you to Malcolm / ‘Cause he was an angel.” It’s hard to imagine that in, say, 1994, when Kurt Cobain’s suicide was met with less serious conversation about mental health disorders and addiction than conspiracy theories about Courtney Love’s involvement.

This sobering up has everything to do with the facts on the ground. Miller’s fatality comes at a time when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that drug overdoses killed more than 70,000 Americans in 2017, a record, overtaking car crashes and gun violence at their peaks. This increase corresponds with use of the kind of synthetic opioids that took their toll on Miller and are pervasive far beyond the young, wealthy, and famous.

The rumblings of that news could be heard in the rise (and rise, and rise) of “SoundCloud rap,” aka “emo rap,” which though it relies on familiar partying tropes, also cleverly subverts them, forcing us to look at the ugly causes and aftermath. No one saw the rapid pop ascendancy of Juice WRLD, an awkwardly named, 20-year-old wunderkind with more hooks in a single track than you can reasonably count. An icon of the streaming-driven hip-hop era, he scored the No. 2 hit in the country with “Lucid Dreams,” an infectious bummer of a breakup anthem.

As other critics have pointed out, he can seem scarily antagonistic toward the woman who spurned him. But Juice WRLD is also, if nothing else, honest to a fault. The more surprising part of “Lucid Dreams” is Juice WRLD’s admission that he self-medicates his sorrow in no uncertain terms. “I take prescriptions to make me feel a-okay / I know it’s all in my head,” he raps, a sign that he’s more self-aware about his baggage than he first seems. The rock bottom is when he moans in a low register, “Now I’m just better off dead.” It’s hard to recall a more queasy-making melody.

Not long after that song came out, Juice WRLD’s peer XXXTentacion was tragically gunned down in June at age 20 amid monstrous allegations that he abused a pregnant woman. His killing seemed to inspire a change of heart in Juice WRLD, who released “Legends” as a tribute to the fellow artist. “I’m tryna make it out,” he says. “I’m tryna change the world.”

Hip-hop is changing, and the world might just be catching up. “I think there’s been great work done publicly to speak about how we might engage differently around mental health,” Carson says. (In a candid New York Times interview last year, Jay-Z talked about how going into therapy made him a better man with more empathy.) “It makes it easier for all kinds of other people to see themselves in that situation rather than do what those artists have talked about on records previously, when seeking out help was perceived to be sort of the ‘weaker’ route,” he says. “To hear your favorite rapper talking about getting treatment, I think it definitely does change how you have that conversation.”

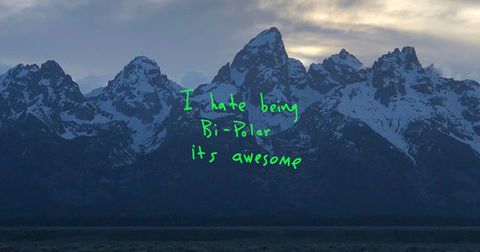

Cudi’s rhymes on Kids See Ghosts help create the space for such a conversation (the ghosts of the album title, it’s clear, are the same ones haunting him every day as an adult). The sentiment even rubbed off on former frenemy Ye, who’s downright apologetic on “Reborn”: “I was off the meds, I was called insane / What an awesome thing, engulfed in shame / I want all the rain, I want all the pain / I want all the smoke, I want all the blame.” Pop’s symbol of narcissism taking a hard look inside himself for the reasons he’s been ridiculed? Hey, it might not be recovery, but it’s a step forward. In the same vein, the standout “Freeee” on Kids See Ghosts is less a brag than wish fulfillment. Starting with a quote from Marcus Garvey praising “man in the full knowledge of himself,” Kanye and Cudi shout over thick guitars, “I don’t feel pain anymore / Guess what, baby? I feel freeee!” Looking inward has helped them step out.

Brockhampton often seems designed to specifically flout the conventions of rap (and pop more generally). De facto leader Kevin Abstract—a 22-year-old, openly gay black man from a Mormon family in Corpus Christi, Texas—likes to tease listeners with references to pleasing his boy. He also gets almost uncomfortably real about the psychic costs of growing up in his position on the band’s gorgeous, genre-less, kaleidoscopic album Iridescence: “And she was mad ‘cause I never wanna show her off,” he raps on “Weight.” “And every time she took her bra off my dick would get soft / I thought I had a problem, kept my head inside a pillow screaming.”

Real good can come from troubled stars who decide to put their guard down. The proof exists in Brockhampton’s “San Marcos,” a tearjerker in which the members take turns uncovering difficult truths. “Suicidal thoughts, but I won’t do it,” Joba sings. “Take that how you want, it’s important I admit it.” It’s just as important for the downtrodden kids who treat Brockhampton like The Beatles to hear the choir at the end euphorically singing, over and over, “I want more out of life than this.” That’s not drowning in misery; it’s a way out.

You can check out the latest casting calls and Entertainment News by clicking: Click Here

Click the logo below to go to the Home Page of the Website

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Twitter

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Facebook

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Instagram

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Pinterest

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Medium