The lack of Black officers in the Army’s key combat commands has diminished the chances for diversity in senior military leadership for years to come, resulting in a nearly all-white leadership of an increasingly diverse military and nation.

The Army, the largest of the armed services, has made little progress in promoting officers of color, particularly Black soldiers, to key commands in the last six years, a USA TODAY analysis finds.

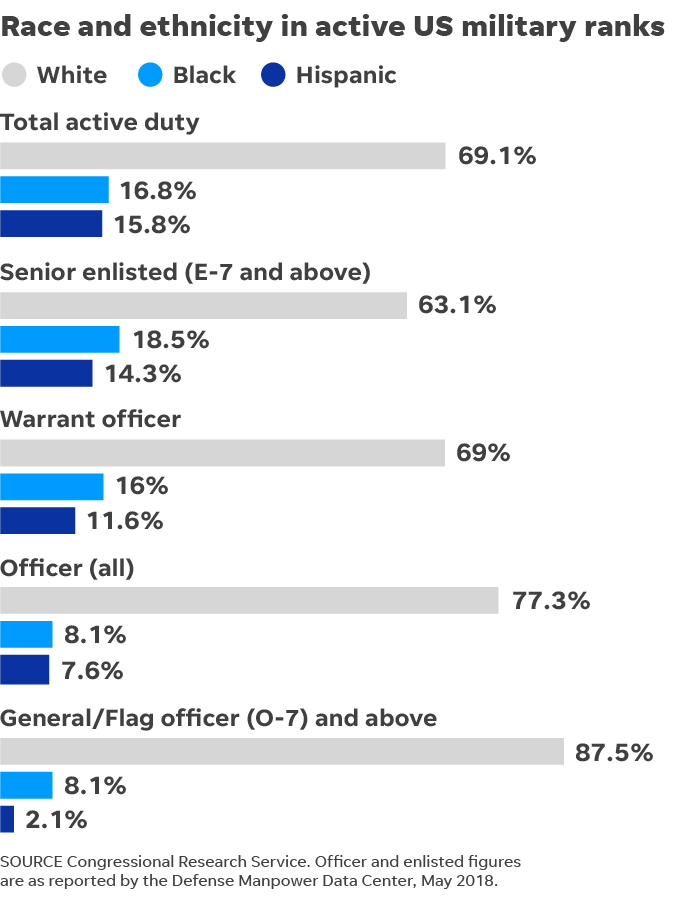

Black people make up 22.7% of enlisted soldiers, 16.5% of warrant officers and 11% of officers on active duty as of July 2020. At the officer levels, this is actually a decrease from 21%, 18.4% and 12.6%, respectively, in 2010. The stakes of fairness and equity are manifest. So, too, is military’s ability to defend the nation.

“The public that we serve should see a reflection of that public in our ranks. From top to bottom and left to right,” said Brig. Gen. Milford Beagle, a Black infantryman who commands Fort Jackson, S.C., the Army’s largest basic training post. “Anytime you have a team that has diversity of thought, diversity of color, diversity of culture – all those things – it’s going to be a much stronger team. I’m a firm believer in that, and it gives our Army a strategic advantage. Looking out to our threats that are out there, they may not necessarily have that. But we do.”

But not enough, some argue. Consider the new commanders of what the Army considers its operational brigades, including front-line units such as infantry, artillery and armor. There are 96 such brigades of around 4,000 soldiers led by a colonel. Just two of the incoming commanders of those units are Black.

In 2014, when USA TODAY first began collecting such data, the Army had no Black colonels leading its combat arms units. Command at battalion and brigade level is practically a prerequisite to leading the Army’s legendary divisions such as the 82nd Airborne, 10th Mountain and 1st Armored. Not coincidentally, the last five Army chiefs of staff have commanded infantry or armored divisions.

The story is only slightly better an echelon below brigade. At the battalion level, where lieutenant colonels are in charge of about 700 soldiers, there are 13 Black battalion commanders out of 231 combat units, or 5.6%.

The Army acknowledges the problem and is addressing it with an array of initiatives. Among them: removing photos of officers from personnel files so that promotion boards are less aware of race. Another sign of progress: more young minority officers choosing combat assignments. Leading the Army’s combat units is a critical stepping stone to the four-star ranks.

The military’s reckoning with racial inequality coincides with national unrest that erupted after the killing of George Floyd, prompting senior military leaders to acknowledge racial inequality in the ranks.

“We must thoughtfully examine our institution and ensure it is a place where all Americans see themselves represented and have equal opportunity to succeed, especially in leadership positions,” chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Mark Milley said July 9 in testimony before Congress.

Then Army Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Milley (now chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) enters Michie Stadium for the 221st graduation and commissioning…

Rep. Jackie Speier, D-Calif., who chairs the military personnel panel on the Armed Services Committee, sponsored a provision to the National Defense Authorization Act that would establish diversity goals, plans to meet them and establish a special inspector general for racial and ethnic disparities.

“It’s 2020, and the Army combat arms only have two Black incoming commanders out of 96, showing that the path to attaining senior rank remains effectively closed to Black soldiers,” Speier said Monday.

She called the finding a “glaring example of structural racism.”

“Failure to cultivate leadership that is truly representative of America threatens troop morale and cohesion,” Speier said. “The strength and future of our armed forces is its diversity. Congress has a duty to ensure military leadership understand and heed that fact.”

But there are no quick fixes. It can take 20 years or more to train a colonel to lead a brigade, about 15 years to groom a lieutenant colonel for battalion command. Along the way, these officers typically have led smaller units at the platoon and company level, acquiring specialized leadership and tactical skills for leading forces into battle.

“There’s no lateral entry for an infantry or armored battalion or brigade commander,” said Lyle Hogue, a top Army official involved in planning and strategy for its inclusion efforts. “We can’t bring them in when they’re 30 years old and pin major or lieutenant colonel promotions on them. What we’re seeing today is a product of what happened 20 years ago.”

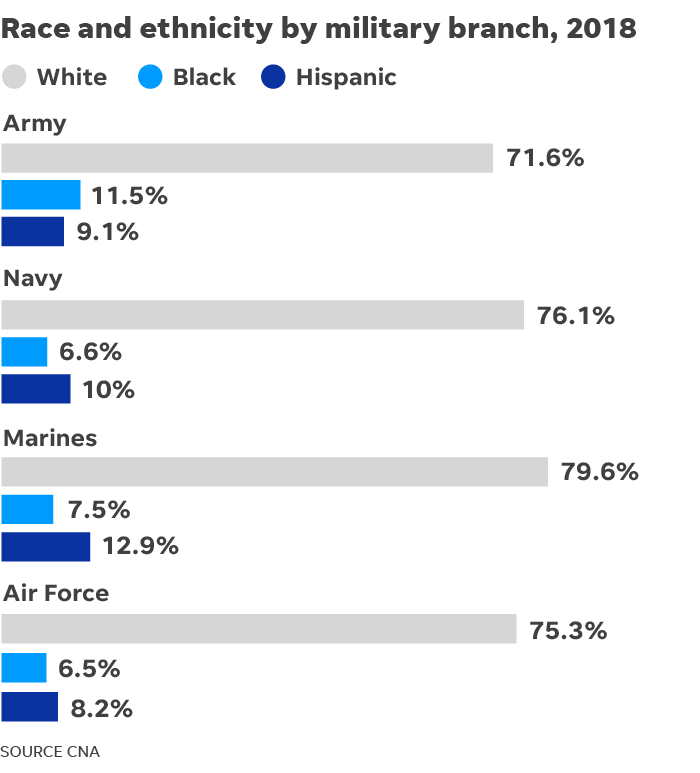

The other services also struggle to diversify their senior ranks.

Consider the Air Force, the other service that provided USA TODAY with demographic data for leadership of its combat units. Three of 85 who command wings of warplanes are Black; 76, or 89%, are white. Being a combat pilot and leading them is a near prerequisite to senior command.

The Marines have the least diversity in their top ranks. Not a single Black Marine has made it to the top four-star rank; six African-Americans reached lieutenant general (three stars); under 20 have received one or two stars, The New York Times reported. Out of 60 Marine generals currently, five brigadier generals and one major general are Black.

‘Heavy burden’ carried by few at the top

One result of the paucity of minority officers at lower ranks is the lack of diversity at the very summit of the military. A select few ascend to the top of the pyramid. With small numbers to start, precious few Black officers attain the top level. In May 2020, there were 19 Black one-star generals in the Army, 15 two-stars, eight three-stars and one four-star, according to Defense Department data. Compare that with white Army generals: 107 one-stars, 90 two-stars, 37 three-stars and 11 four-stars.

Gen. Michael Garrett, commanding general of Forces Command, is the Army’s lone Black 4-star officer. Garrett is a career infantry officer.

Look at the composition of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, which dates to 1942. It is made up of the service chiefs from the Air Force, Army, Marine Corps, Navy and National Guard Bureau. At the very top sit the chairman and vice chairman, the top two officers in the military.

This month, the first Black general to lead one of the services, Gen. Charles Brown, an F-16 pilot, was sworn in as Air Force chief of staff. Army Gen. Colin Powell, the first and only Black Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, made the leap to the top without having served as chief of staff of the Army. He was also an infantry officer.

Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. testifies on his nomination to be Chief of Staff, United States Air Force, before the Senate Armed Services Committee in…

Brown spoke openly about discrimination in the military.

“I’m thinking about how my nomination provides some hope, but also comes with a heavy burden,” Brown said. “I can’t fix centuries of racism in our country, nor can I fix decades of discrimination that may have impacted members of our Air Force.”

Apart from Brown, the rest of the service chiefs, the chairman and vice chairman are white. None are women, either. Combat jobs opened fully to them in 2015. Hispanics make up about 16% of all active-duty military, according to the Department of Defense, but Latinos are only 8% of the officer corps and 2% of general/flag officers, according to a 2019 report by the Congressional Research Service.

From segregation to discrimination

Why do so few Black officers lead combat units?

When Beagle’s great grandfather Walter Beagles walked through the gates at Fort Jackson in 1918, he entered a segregated Army that relegated Black soldiers to labor units.

“They weren’t thought to be smart enough to be in combat arms,” Beagle said.

It would be 30 years before the armed services integrated. Even 100 years later, commanders like Milford Beagle are few and far between.

A system that didn’t afford opportunity to Black and minority officers in combat units explains part of the problem. After integration, the military was slow to accept minority officers. There’s also the matter of choice.

Parents, clergy, coaches, even soldiers often discourage aspiring minority officers from joining combat units, Beagle said. Heavy casualties among African Americans, particularly early in the Vietnam War, and the prospect of better post-military employment options made non-combat units such as logistics a preferred choice.

Casualty statistics from Vietnam show how those perceptions formed, according to a report from the Congressional Research Service. In 1966, Blacks accounted for 22.4% of all troops killed in action in 1966 while making up 18% of the Army and about 17% of the Marine Corps. By the end of the war, Black war deaths had dropped to 12.4% of the total. But the perception persisted.

“To this day, you still may have influencers from the Vietnam era,” Beagle said.

The relative few Black officers who rose through the ranks in the 1980s and 1990s often saw few minority officers as role models to encourage them. There is also evidence of systemic racism in the military’s criminal justice system. This spring, the Air Force acknowledged that young enlisted Black airmen were twice as likely to face punishment as their white counterparts.

Interpersonal racism is also an issue. A 2016 study published in the peer-reviewed journal Sage found that white military veterans expressed more “virulent attitudes” toward African Americans relative to their civilian counterparts.

Many Black troops do succeed, but not without overcoming obstacles.

Lt. Gen. Gary Brito was one of three Black ROTC students at Penn State University in the mid-1980s. Brito recalled that his fondness of the outdoors and interest in leading soldiers meshed well with infantry.

“Was going to do four years and get out,” he said. “Turned into 10, turned into 20. Still love what I do. That’s what inspired me.”

Brito, who is now the Army’s top personnel officer, does not recall overt racism blocking his ascent but allowed that his path was “a little more challenging than for others.” He adopted, he said, the attitude that “any obstacle can be breached.”

Retired Maj. Gen. Dana Pittard graduated from West Point in 1981 and found that he was actively discouraged from climbing the ranks of armor, his career field. As a young officer in the 1990s, he had been assigned to recruiting command, a move that would have limited his career options.

“I said, ‘This is crap,” Pittard said. “‘This is bull crap.'”

Instead of recruiting, Pittard chose to enroll in the School for Advanced Military Studies at the Army’s Command and General Staff College. He knew he’d find a combat assignment after graduation. The experience taught him that unless the Army actively encourages minority officers and offers them challenging assignments, diversity in its senior ranks will be left to chance.

“If you keep making assignments by accident, and not on purpose, you’re going to get the same kind of by-accident results that we see now,” Pittard said.

‘Soldiers need to … see leaders that look like them’

The Army’s new initiatives to diversify its senior ranks aim to improve recruiting, mentoring and retaining minority soldiers, said Marshall Williams, the Army’s principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army for Manpower and Reserve affairs. Elimination of photos for review by promotion boards is on the leading edge of the effort.

The need for more minority officers becomes evident as incoming recruits come from increasingly diverse backgrounds, he said.

“We need diversity because those soldiers need to look up and see leaders that look like them,” Williams said.

Young minority officers from combat units have success at persuading cadets at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and ROTC students at colleges to pursue careers in infantry, armor and aviation. But assigning a promising minority infantry or artillery officer to teach military science and mentor students can delay or derail the officer’s career, said Anselm Beach, the deputy assistant secretary of the Army for equity and inclusion.

“Then you reduce that pool, and you have a structural issue,” Beach said. “Those are things we are looking at.”

But there are some reasons for optimism. Since 2014, the Army has seen a slow but generally steady increase in the number of young Black officers choosing combat assignments, according to newly released data. Officer Candidate School, ROTC programs and West Point have all seen increases. At West Point, less than 6% of new officers had joined combat units. In 2020, more than 10% had chosen that path. College campuses with ROTC programs registered an increase from 6.7% to 9.4%.

One of those university graduates who accepted an infantry assignment is Beagle’s son, 1st Lt. Jordan Beagle.

You can check out the latest casting calls and Entertainment News by clicking: Click Here

Click the logo below to go to the Home Page of the Website

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Twitter

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Facebook

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Instagram

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Pinterest

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Medium